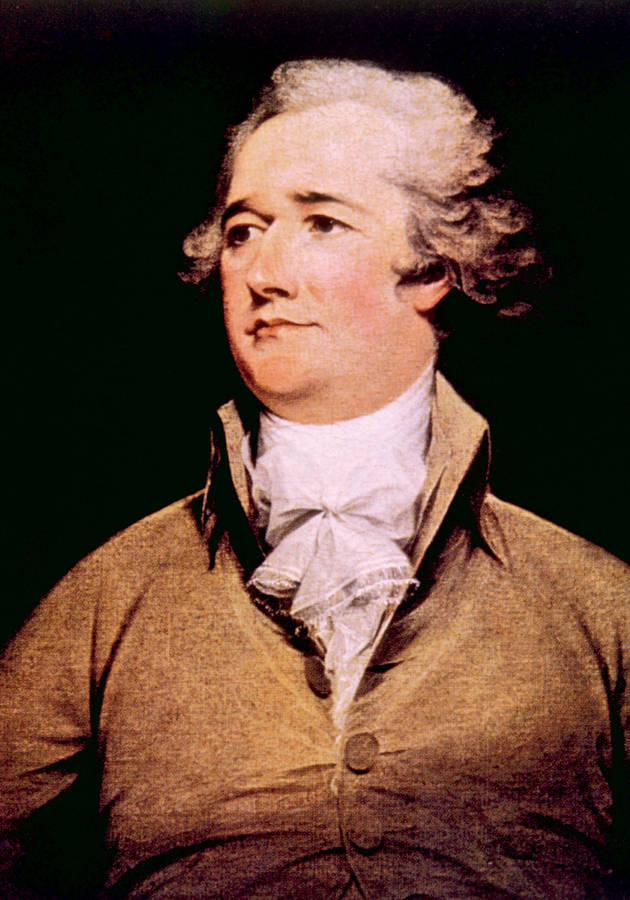

“How does a bastard, orphan, son of a whore and a Scotsman – dropped in the middle of a forgotten spot in the Caribbean by Providence – impoverished, in squalor, grow up to be a hero and a scholar?” Well, get ready to find out as we delve into Ron Chernow’s masterful 900-page biography of Alexander Hamilton, one of the least understood and most commendable of America’s Founding Fathers!

The ten-dollar Founding Father without a father

The birth of Alexander Hamilton is shrouded in several mysteries; in the absence of surviving records, at least one of them will probably remain unsolved for the foreseeable future, if not forever.

Later in life, he often claimed that he had been born on the tiny island of Nevis in the British West Indies on January 11, 1757. The place and the day seem correct, but the year is probably wrong: evidence uncovered in the 20th century suggests that he may have been two years off in his estimations. For example, in 1768, a probate court in St. Croix in the Virgin Islands listed his age as 13, and he himself gave it as “about 17” when he sent a poem to the editor of a St. Croix newspaper in 1771. As a result, most recent historians opt for 1755 as Hamilton’s year of birth, but the baffling matter is far from settled. In fact, as Chernow writes, few questions bedevil Hamilton biographers more than this date.

In any case, it is well-known that both Alexander and his older brother James Jr. were born out of wedlock to James A. Hamilton, a Scotsman, and Rachel Faucette, a married woman of half-British and half-French Huguenot descent. Owing more to Caribbean folklore than evidence or truth, another mystery has formed around Rachel’s race, because of which – to this day – millions of Americans believe that Hamilton’s mother had black ancestry, making Alexander one-quarter or one-eighth black descendant. However, Chernow writes, “Rachel was invariably listed among the whites on local tax rolls. Her identification as someone of mixed race has no basis in verifiable fact.”

Living without a family since he was a child

Stigmatized as a bastard, Hamilton had to endure a difficult childhood; barred from Anglican instruction on account of his illegitimate birth, he probably didn’t even have a chance to be formally schooled. Things went from bad to worse almost as soon as Alexander entered the second decade of his life, when – in just three years – destiny forced him to trade his low social status as a bastard with an even more anguishing one: a disinherited orphan.

First, when he was 11, his father abandoned the family, and just two years later, his mother died of an unspecified illness, believed to be yellow fever. Alexander too contracted the disease but survived. Soon after, he and his brother James were left penniless and buried in heaps of unpaid bills, as their mother’s entire estate was awarded by the court to her husband Peter Levien, who thought of the Hamilton boys as nothing more than “whore-children.”

Barely teenagers, the two brothers were thrown upon the mercy of friends, family, and community. Little did they know that there were a few more items on “the grim catalog of disasters” that life had prepared for them.

Left with nothing but ruined pride

After Rachel’s death, her sons were placed under the legal guardianship of their 32-year-old first cousin Peter Lytton. Unfortunately, on July 16, 1769, Peter “stabbed or shot himself to death,” leaving nothing to the boys in his quickly drafted will.

In the aftermath, Peter’s crestfallen father, James Lytton, tried to aid the orphaned children, but legal obstacles resulting from the suicide thwarted his well-meaning attempts. To make matters worse, just a month later, James died as well, making no provision for his nephews Alexander and James in his will, penned just a few days before his death. By the end of 1769, destiny deprived the brothers of their aunt and their grandmother too.

“James, 16, and Alexander, 14, were now left alone, largely friendless and penniless,” comments Chernow. “At every step in their rootless, topsy-turvy existence, they had been surrounded by failed, broken, embittered people. Their short lives had been shadowed by a stupefying sequence of bankruptcies, marital separations, deaths, scandals, and disinheritance. Such repeated shocks must have stripped Alexander Hamilton of any sense that life was fair, that he existed in a benign universe, or that he could ever count on help from anyone. That this abominable childhood produced such a strong, productive, self-reliant human being – that this fatherless adolescent could have ended up a founding father of a country he had not yet even seen – seems little short of miraculous.”

...And he wrote his first refrain, a testament to his pain

But even at that age, Alexander showed glimpses of remarkable intellect and profound understanding of the world. Fluent in both English and French, he had been an avid, omnivorous reader ever since he could first form a sentence. The upstairs living quarters of his mother’s house held 34 books, some of which – such as Alexander Pope’s poetry, Machiavelli’s “The Prince” and Plutarch’s “Lives” – left an indelible mark upon the boy’s psyche.

As his brother James apprenticed with a local carpenter, Alexander became a clerk at a local import-export firm named Beekman and Cruger. In just two years, he learned so much about international relations, trade policy, and monetary exchange that the owner of the company wasn’t afraid to leave him in charge of the company for five months while he was at sea. He was just 16 years old at the time.

Just a year later, on August 30, 1772, Hamilton wrote a letter to his father detailing the disastrous effects of a hurricane that had struck St. Croix. A local minister and journalist by the name of Hugh Knox was so impressed with it that he published the letter in The Royal Danish-American Gazette. Suddenly Hamilton became a sensation: everybody – including the island’s governor – was inquiring about him.

Soon enough, local businessmen organized a subscription fund to support Alexander and send him to North America to be educated. That very same year, in October, he disembarked in Boston and proceeded from there to New York City, where, in the autumn of 1773, he entered King’s College. Not long after, Samuel Adams’ Sons of Liberty organized a protest against British Parliament’s tax on tea. A revolution was in the making, and Hamilton wasn’t going to stand aside and watch.

Blowing them away: an orator, a soldier, and a right-hand man

On July 6, 1774, at the grassy Common near King’s College called The Fields, Alexander Hamilton made his first public appearance, endorsing the Boston Tea Party and colonial unity against unfair taxation, while also advocating for a boycott of British goods. Such actions, he triumphantly concluded, “will prove the salvation of North America and her liberties.” The power of his speech and the fervor of his words left everybody silent and transfixed; overnight, he became a youthful hero of the cause and was recognized as such by many revolutionaries.

As always, Hamilton wanted more. When later in the year, under his pen name “A Westchester Farmer,” Church of England clergyman Samuel Seabury published a pamphlet promoting allegiance to the British crown, Hamilton responded with his first political writings, “A Full Vindication of the Measures of Congress” and “The Farmer Refuted.” Just two months after the latter one was published, the Battles of Lexington and Concord marked the military beginning of the American Revolution.

Hamilton was quick to take part. He demonstrated eye-catching bravery on several occasions, most notably during the battles of Trenton and Princeton. On January 20, 1777 – just two weeks after the conflict at Princeton – George Washington personally invited the 22-year Alexander Hamilton to join his staff as an aide-de-camp – that is to say, confidential assistant. In a very brief period, Alexander became something more: Washington’s right-hand man. Recognizing Hamilton’s exceptional abilities and intellectual capacity, Washington gave him huge autonomy, so this young and cocky Caribbean wunderkind not only read and composed most of the letters of the nation’s de facto leader but also regularly gave him advice on how to proceed with the war.

Ladies – they delighted and distracted him

While stationed in Morristown, New Jersey, in the early months of 1780, Hamilton met Elizabeth Schuyler, daughter of General Philip Schuyler. By the end of the year, the two married each other. Over the following two decades, Elizabeth gave birth to seven children: Philip, Angelica, Alexander Jr., James Alexander, John Church, William Stephen, and Eliza. In 1801, the couple’s oldest and most promising son Philip died in a duel at the age of 19, after attempting to defend his father’s honor against a New York lawyer named George Eacker. To preserve his memory, Elizabeth and Alexander gave the name Philip to their eighth and last child – born just a few months after the death of his namesake.

The marriage of the two wasn’t idyllic, but their relationship was one of mutual respect. Elizabeth accepted her husband’s flirtatiousness, and he cherished her enough to consult her on many important political and family matters. However, he didn’t cherish her enough to be faithful. On the contrary – there were plenty of rumors regarding his extramarital escapades. One of them reached the newspapers, making Hamilton the first major American politician to be publicly involved in a sex scandal.

The affair itself took place between 1791 and 1792, while Elizabeth was pregnant with the couple’s fifth child. Over an entire year, Hamilton had an illicit year-long sexual relationship with a 23-year-old married woman, Maria Reynolds. To make matters worse, she lied to him about being abandoned, when in reality, her husband James was well aware of the liaison and even supported it. His goal? To gain blackmail money from Hamilton. And he did, on several occasions, for a total of $1,300 – a third of Alexander’s annual income!

The affair might have never entered the public eye if it wasn’t for James Reynolds’ arrest in 1797 for an unrelated offense. Journalists discovered the connection between him and Hamilton, and Alexander’s name found its way to the newspapers. Shortly after a newspaper accused him of using federal funds to illegally speculate in government securities with Reynolds, Hamilton decided to admit to the affair. In a way, he didn’t really have a choice: the money he had paid to Reynolds was hush money, so by coming clean about his infidelity, he was successfully refuting the more serious accusations against him. Even so, it is often argued that the sex scandal effectively ruined Hamilton’s chances of ever becoming the president.

Young, scrappy and hungry – and dreaming of glory

Immensely talented and ambitious, Hamilton always aimed high. Not long after becoming Washington’s right-hand-man, he started pressing the general-in-command to give him a more active role in the war. He wasn’t only tired of dealing with routine duties at headquarters, but he was also aware of the fact that being courageous on the battlefield was his best shot at advancing in life. After several refusals, he used a trivial quarrel to break with Washington and leave his staff – not long after getting married.

Destiny had different plans for Hamilton: just a few months later, Washington called him back, giving him command of a light infantry battalion in the division of Marquis de Lafayette, the hero of the two worlds and America’s favorite fighting Frenchman. In October 1781, Hamilton was given the chance to prove his worth: during the siege of Yorktown, he led a surprise and successful night assault on a British stronghold. This resulted in a decisive victory over the English and earned Hamilton the reputation he so desperately yearned for.

After the war, Hamilton studied law, and in 1783, he set up a practice as an attorney in New York City. Four years later, he was chosen as one of the three delegates from New York to a federal convention held in Philadelphia with the objective of overhauling the Articles of Confederation. On June 18, he gave a “brilliant, courageous, and, in retrospect, completely daft” six-hour speech advocating an unpopular view: a strongly centralized government. Just as he had expected, the speech drew immediate criticism, and to this day he is often blamed for wanting to create a monarchy. It wasn’t like that.

“Of all the founders,” Chernow explicates, “Hamilton probably had the gravest doubts about the wisdom of the masses and wanted elected leaders who would guide them. This was the great paradox of his career: his optimistic view of America’s potential coexisted with an essentially pessimistic view of human nature. His faith in Americans never quite matched his faith in America itself.”

Write day and night, like you’re running out of time

In the end – and probably for the better – Hamilton didn’t have a lot of influence on the final look of the U.S. Constitution, a landmark document in the history of modern democracy. However, he played a very important role in its ratification.

With the help of Founding Fathers James Maddison and John Jay, he co-wrote “The Federalist Papers,” a collection of 85 articles and essays interpreting and defending the Constitution before the American people and published under the collective pseudonym “Publius.” Due to illness, Jay wrote just five of the essays; Maddison, 29; and Hamilton, 51! In just seven months! They would become his best-known writings and are still used today as some of the most important references for Constitutional interpretation.

This herculean labor wouldn’t go unnoticed. On September 11, 1789 – about five months after George Washington’s unanimous election as the first president of the United States – Hamilton was appointed the first secretary of the United States Treasury. He successfully argued for the federal government’s assumption of state debts and the creation of a national banking system on the grounds that this would provide credit and currency for the country’s economy.

Once again, some saw Hamilton’s views as undemocratic – most notably, his former ally Maddison and the nation’s first secretary of state, Thomas Jefferson.

You must get through to Jefferson

In contrast to Hamilton, Jefferson opposed a national debt – preferring that each state retire its own – and believed that any centralizing policies would place too much power in the hands of the federal government. His strenuous opposition to Hamilton’s plans led to Washington dismissing Jefferson from his cabinet.

The conflict tells us a lot about the characters of the two Founding Fathers. “Where Hamilton looked at the world through a dark filter and had a better sense of human limitations,” Chernow expounds, “Jefferson viewed the world through a rose-colored prism and had a better sense of human potentialities. Both Hamilton and Jefferson believed in democracy, but Hamilton tended to be more suspicious of the governed and Jefferson of the governors.”

In this case, Hamilton emerged as both the immediate victor and the one absolved by history: founded in 1791, the First Bank of the United States succeeded in fueling economic growth and proved to be a turning point in the formation of a new global superpower.

Be that as it may, the divide between Hamilton and Jefferson only deepened in the following years, and – exacerbated by differing stances between the two regarding the participation of the United States in the war between Great Britain and France – it spawned the creation of the first two national parties in the United States: the Democratic-Republicans, with Jefferson and Maddison at the helm, and the Federalists, led by Hamilton and John Adams.

On January 31, 1795, Hamilton left his Treasury post, but he continued to be consulted by Washington and his cabinet on most matters of policy. When Washington decided to retire, it was Hamilton who wrote his famous “Farewell Address,” given in September 1796. Even so, the Federalist leaders chose to successfully nominate John Adams for the presidency at the next elections. This – among other things – created a schism within the party. The feud between the two resulted in Jefferson defeating Adams in the presidential elections of 1800 and the eventual collapse of the party, making Adams the only Federalist president in history.

The fool who shot him: Vice President Aaron Burr

At the presidential elections of 1800, Hamilton worked against his party, preferring Jefferson to Adams. He also preferred Jefferson to his Democratic-Republican running mate Aaron Burr. So, when the two won an equal number of electoral votes, Hamilton convinced several Federalists to switch their support from Burr to Jefferson, giving his old rival the victory.

But Burr was an even greater rival of Hamilton. Alexander thought him “unprincipled both as a public and private man” and hated him for his equivocality. “I take it he is for or against nothing but as it suits his interest or ambition,” he wrote in a 1792 letter. “I feel it a religious duty to oppose his career.” Burr felt something similar

He stood by his word until the very end. In 1804, when Burr ran for governor of New York State, Hamilton campaigned against him as undeserving of the position. After he lost, Burr asked Hamilton to apologize for some of the insults, but – impetuous as always – Alexander refused to back down. So, Burr challenged him to a duel that occurred on July 11, 1804. Alexander purposefully threw away his shot; Burr wasn’t as gentlemanly and mortally wounded Hamilton, who died the following day.

Final Notes

“No immigrant in American history has ever made a larger contribution than Alexander Hamilton,” writes Chernow halfway down his authoritative and magisterial biography of the Founding Father.

And indeed, “the magnitude of Hamilton’s feats as treasury secretary has overshadowed many other facets of his life: clerk, college student, youthful poet, essayist, artillery captain, wartime adjutant to Washington, battlefield hero, congressman, abolitionist, Bank of New York founder, state assemblyman, member of the Constitutional Convention and New York Ratifying Convention, orator, lawyer, polemicist, educator, patron saint of the New-York Evening Post, foreign-policy theorist, and major general in the army.”

As strange as it may sound, Chernow’s “Alexander Hamilton” covers all of these facets – and does so in depth. A truly astounding, articulate, and ageless work.

12min Tip

If you haven’t watched it already – which we doubt – watch the “Hamilton” musical. It’s inspired by this book – and it’s absolutely amazing!